Is the mind set or flexible?

The role of emotions and mind in everyday life

Aim

The following is a summary of literature on different models for and perspectives on mindsetting, as well as on the progressive evolution of emotions, with the aim of determining whether emotions are expressions of fixed states of mind arising out of an individual‘s existence, or whether they are the changeable results of new knowledge, intentions, (logical) convictions, and decisions.

The aim of this article is…

- to investigate the foundation of emotions from a humanistic and psychological perspective, based on literature taking a human resources approachto showcase different models of behaviour for daily work and leadership, focusing on emotions and individual drive

- to help understand different perspectives on behaviour – for both yourself and for others, whether you are a follower, learner, leader, or learning facilitator

- to discuss the relational impact of perception, intentions, and behaviour

- to investigate professional and corporate perceptions and values when it comes to organisational mindsetting and the impact of changing one’s mind in a leadership role or task

- to inspire emotionally agile work for leaders and others more generally

“Why do we always judge others by their behaviour – and ourselves by our good intentions?” (Irish proverb)

Introduction

Everyday we meet other people and, whether consciously or unconsciously, we take note of their behaviour – and mirror their behaviour in our own idiosyncratic way. Based on their gestures and expressions, we judge whether their behavior is ‘reasonable’, ‘predictable’, ‘strange’, or even ‘silly’. From the moment we make this decision, our thoughts revolve more around ourselves as observers than around the person we are observing – unless we take the time to ask the person about their behaviour and the intentions. If we do make the effort to ask, usually one of at least two different outcomes occurs:

- as the observer, we understand a little bit more about the other person, albeit still as a combination of our own experiences, knowledge, values, and perceptions

- the other person will learn more about themselves as our questions and interest prompt them to reflect on the previously unconscious emotions and thoughts underlying their attitudes and behaviour.

Throughout various leadership theories, the concept of ‘mindset’ has been referred to in different ways: assumptions, mental perceptions, mental maps/landscapes, attitudes, and beliefs, etc. Various theoretical attempts have been made to understand the connection between personality, attitudes and emotions, and potential changes of behaviour that arise. To take another angle, mindsetting could be analysed from any of the following perspectives: individual, leadership, organisational (also cultural, prejudicial, etc.).

While modern and post-modern leadership is closely related to (personal and corporate) development, the impact of mindsetting on learning should also be taken into consideration. Modern HR leaders are often more responsible for and occupied with the personal development of employees than the attainment the business goals. This raises the big question of how obstructive attitudes can be addressed and constructive attitudes supported amongst employees and other stakeholders.

This article will therefore explore how different psychological and social theories explain the potential impact of mindsetting when it comes to perceiving and reacting to the emotions of others.

Mindset – what is that?

A Mindset is a worldview, the way in which one experiences reality and forms perceptions. It is undergirded by one‘s assumptions, limited by one‘s prejudices, and supported by one‘s values (developed from Anderson & Anderson )

In decision theory and general systems theory, a mindset is a set of assumptions, methods, or notations held by one or more people or groups of people. This means that institutions, professional groupings, and organisations can also develop and use organisational mindsets. These may or may not be aligned with the specific mindsets of the individuals involved.

Minds are mostly set by repeated, and thereafter generalised, impulses, whether they are consciously observed and articulated or not. Generalised impulses on an individual or corporate level in a group or organisation develop into assumptions, and human minds then tend to look for new impulses to support or strengthen existing assumptions, rather than contradicting these. These assumptions shape mindsets, which in turn can become fixed if they are not challenged by new or contradictory perspectives, or if they fail to take other interests into account.

For example, the main goal of a school from the parents‘ perspective might be ‘learning’, from the teachers‘ perspective ‘teaching’, from the secretary‘s perspective ‘administrating’, and from the headteacher‘s or accountant‘s perspective ‘keeping to the budget’. Each perspective is ‘right’ from its own point of view, but they can be discussed by the stakeholders. What would the mindset of one, four, or all of the pupils at the school be?

Fixed or growth mindset

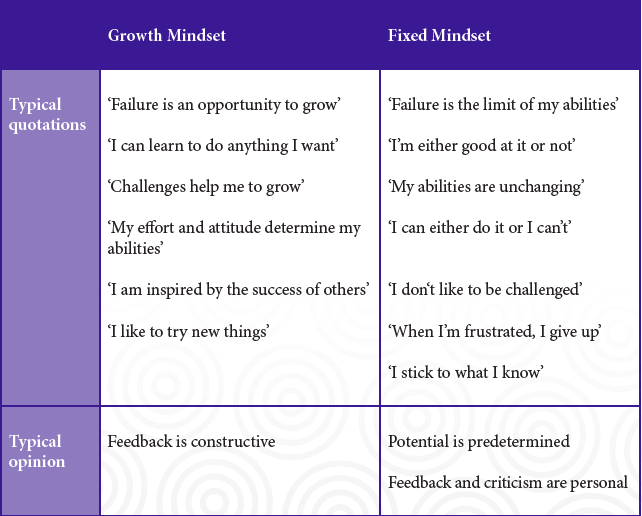

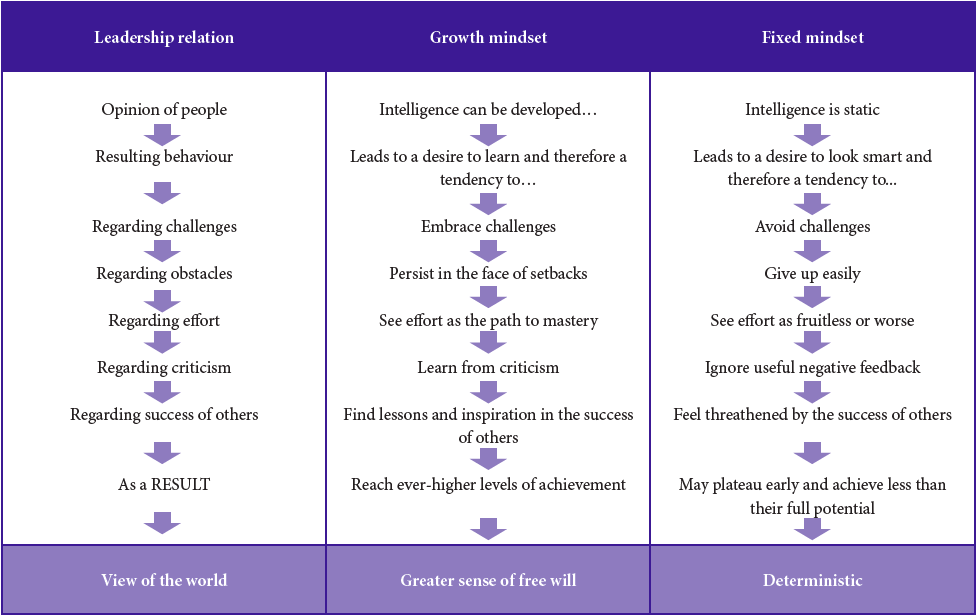

Carol S. Dweck has spent many years investigating how individual mindsets develop and how these mindsets can be challenged, disturbed, or exercised. Her research has resulted in a model of two categories of mindsets: the fixed mindset (difficult to challenge and change) and the growth mindset (constantly evolving):

Dweck also explains the relationship between leadership approaches and behaviour depending on which mindset is adopted.

Leaders with fixed mindsets think that they are important at work simply because they exist. They can be described as DIMINISHERS.

Leaders with a growth mindset appreciate the development of their employees and tend to render themselves redundant. They are MULTIPLIERS.

(Liz Wisemann 2009)

Jung’s personality preference function : Feeling

Carl Gustav Jung, the ‘grandfather’ of many personality type studies and psychometric programs, began by distinguishing between introverts and extroverts, and stating that this orientation is difficult to change. Whether this orientation is congenital or evolved socially or culturally continues to be discussed. It is clear, however, that the introvert-extrovert divide impacts an individual’s empathic abilities and basic values. Could this be applied to mindsetting?

One of the categories in Carl Gustav Jung’s model of different personalities model is the decision-making preference ‘Feeling’, as opposed to ‘Thinking’: in other words, whether the person mainly makes decisions on the basis of their head or heart. This decision-making preference can be seen in an individual‘s vocal expressions, interests, and personal or professional appearance. So does this mean that the ability to identify and show an interest in other people’s emotions and well-being is an inherent ability or the result of training and an increased awareness?

Ever since Jung released his first theses about personality types, there have been ongoing discussions about the origin of different character traits. Are preferences determined by genetics, in place before birth, or are they socially or culturally shaped throughout an individual‘s lifetime?

Jung’s theories of personality types have, in fact, shaped the development of numerous psychometric tools, most of them used for recruitment, competencies assessments, team building and development, and ideal groupings, with the aim of optimising groups and taking complementary group settings into account.

But how does this correspond to social behaviour theories – and with business models for workers and leadership or management?

MacGregor’s XY theory of management – a professionally applicable version of mind-setting?

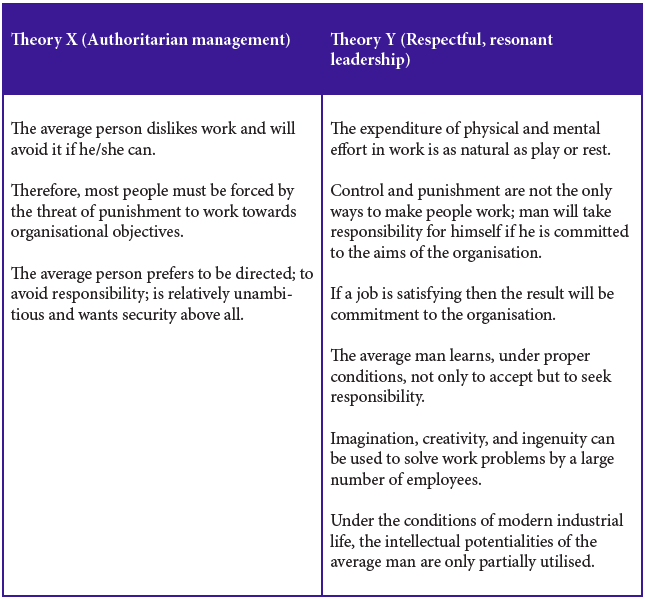

Douglas McGregor first proposed his XY Theory in 1960 to help people develop a more positive management style. The model shows two different ways of viewing people and could well have been the impetus behind modern leadership theories, as opposed to of the previously accepted management styles.

McGregor’s ideas suggest that there are two fundamental approaches to managing people. Many managers tend towards theory x, and generally get poor results. Enlightened managers use theory y, which produces better performance and results, and allows people to grow and develop.

McGregor’s ideas significantly relate to modern understanding of the psychological contract, which provides many ways to appreciate the unhelpful nature of X-Theory leadership, and the useful, constructive, and beneficial nature of Y-Theory leadership.

The theories of X and Y are still frequently referred to in the field of management and motivation and, whilst more recent studies have questioned the rigidity of the model, MacGregor’s XY Theory remains a valid basic principle of a leader’s point-of-view from which to develop a positive management style and techniques. McGregor’s XY Theory remains central to organisational development and to improving organisational culture.

A question to think about: Is MacGregor’s theory simply a repetition of the mindset theory, phrased in business terminology?

By extrapolating from (working) individuals to larger groups, organisations, or even national cultures, we can look at different models for (corporate) mind-setting.

‘The world of the manager is complicated and confusing. Making sense of it requires not a knack for simplification but the ability to synthesise insights from different mindsets into a comprehensive whole.’

Howard Gardner’s intelligences or mindsets

Howard Gardner is mostly known for developing theories about multiple intelligences, investigations that have lead to a more general approach to how individuals have the potential to grow in different directions, depending on basic persistent strengths.

After some years of working on his theory of multiple intelligences, Gardner defined and described an original set (mathematical-logical, verbal, bodily-kinaesthetic, musical, and special), along with social or relational intelligences (intra- and interpersonal), and then spiritual, naturalistic, and existential intelligences, which he introduced later. These categories were later also criticised by Gardner himself .

These multiple intelligences are most relevant for individuals, but other perspectives of mindsetting include corporate and organisational spheres and their corresponding leadership approaches. In his book Changing Minds , Gardner narrates his reflections and reactions when working with corporate institutions, in which management teams want to shape the mindsets of their employees and other stakeholders.

Mind-setting and leadership – and vice versa

Howard Gardner himself worked on critical and constructive feedback, which led to a 2007 publication of a new theoretical model, entitled Five Minds for the Future . This work outlines the specific cognitive abilities that should be sought and cultivated by leaders in the years ahead.

Gardner outlines the following mindsets:

- The disciplinary mind: the mind that organises, links structures, and makes use of primarily logical thinking, including most common philosophical theories as science, mathematics, and history. The disciplinary mind also covers at least one professional craft.

- The synthesising mind: this category covers the ability to combine and integrate different disciplines or spheres into a coherent whole, and how to master and communicate this integration to others.

- The creating mind: the creating mind can describe, illustrate and articulate upcoming ideas, problems, questions, and phenomena, mostly without any pre-existing relationship.

The above three minds all relate to the working individual, group, organiation, or cohort – i.e. the ‘working society’. These three categories are all useful for planning for the future. Gardner also defined two just as important mental categories, although these revolved more around individual than collaborative existence:

- The respectful mind: an awareness and accepting appreciation of differences between individuals, including the need for complementation between different yet equally contributing human beings, groups, and cultural sharpening organisations.

- The ethical mind: the skill of being a world citizen, able to distinguish between ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ and to contribute to and remain loyal to rules, decisions, and individual responsibilities as workers and/or citizens.

Gardner has developed his mind categories on the basis of diverse case studies in private and corporate environments in order to illustrate his ideas and to inspire the citizens of today and tomorrow for lifelong learning, whether as learners, learning facilitators, or leaders.

This leaves us with the following question: are Gardner’s mental states more of an ideal combination of corporate values and qualifications for the future life of organisations and cultures? Is there any link between his mind theory, his previous intelligence categories, and the post-modern ideals of a resonant and reflective leadership ideal?

The answer can perhaps be found in one of Gardner‘s much earlier publications: Changing Minds . Here, Gardner introduces the difficulty of working with other people‘s mindsets, explaining that he was once contacted by a corporate business and asked to change the mindsets of their employees and to give them a perspective accepted by the leadership team. Gardner found it impossible to change the minds of others. The best that can be done is to provoke or disturb other people’s mental assumptions, thereby raising their awareness and prompting them to consider the reliability and validity of their assumptions. This might result in a later decision or change of mind. In other words, you can motivate others to adopt a more flexible mindset, but you cannot force them to change.

Six categories of mindsets

We have now looked at mindsets and mind-setting from an individual perspective, as well as from the perspective of an employer or leader, including the possibility of gradually changing mindsets over time to impact the individual sphere. Global history has shown that the mindset of a single charismatic and verbally intelligent person can impact the collective mindset of an entire group of people. The term ‘charismatic’ brings us to a discussion of how much our perspectives impact our emotions, and vice versa.

The development of leadership approaches has also been the development of the trends of leaders’ perspectives towards their work and towards the people they are leading (this is looked at in more detail in another article). Postmodern leadership theories focus more on mindsets, motivation and emotions than earlier theories. Corporate groups and volunteer organisations are getting better at thinking about and taking notice of the way in which they treat their staff.

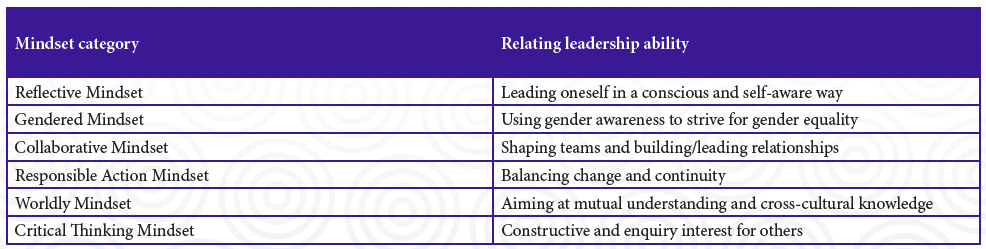

WAGGGS , an international NGO for girls and women, is currently developing their second generation leadership approach in conjunction with Jonathan Gosling from Exeter University. They have outlined 6 mindset categories that are important for future leadership and life in general:

These mindsets, based on the ideas of Gosling and Mintzberg , promote leadership approaches that aim to minimise ‘false’ or undocumented assumptions. They could therefore be useful for starting a discussion about the flexibility of human minds in a post-modern context. They could be used to question the idea of ‘fixed’ mindsets by raising awareness about where assumptions come from and thereby gradually changing these assumptions into useful and constructive perspectives for individuals and their surroundings.

Action without reflection is thoughtless;

Reflection without action is passive

How to lead, taking mindsets into consideration (David and Congleton / Hayes )

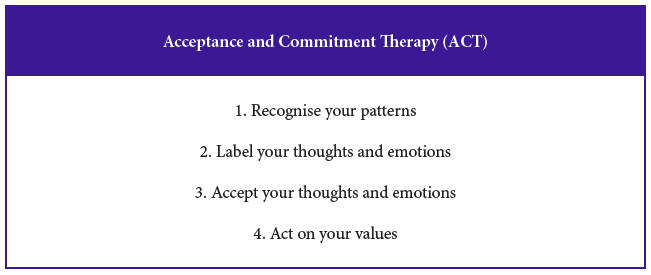

In a toolbox for leaders on exercising the flexibility of mindsets, whether fixed, growth, or any other kind of mindset (to use Dweck‘s terminology), David and Concleton give a fairly simple recipe in 4 stages:

This recipe follows the recent developments discussed above about the need for awareness of and a potential change in one’s own mindset.

One way to be constantly exercising one’s mindset is to take time to regularly reflect. You could, for example, plan a brainstorming session for your stakeholders about a (leadership) challenge. If needed, you could invent some new and surprising stakeholder roles. Spend time reflecting on the potential mindsets and attitudes of each of the stakeholders. Your responses to the challenge should correspond to the wide range of stakeholder mindsets.

A conscious leader, using these exercises, can develop quality leadership that takes embedded mindsets into account.

Mental model mapping

Lars Kolind, a Danish leadership theorist and practitioner, shares a toolbox for postmodern leaders/managers in his book ‘The Second Cycle’, in which he refers to a mindset as a ‘mental model’. Kolind claims that mapping the mental model can make the ‘owner’ aware of its relevance and actuality, and that this mere awareness can prompt change or anchor an attitude. The mental model mapping process is aimed at prompting awareness of a corporate mental model in a potentially fatigued organisation with the following 5 steps:

- Map the existing mental model of any aspect of the organisation and summarise it in a short sentence or in a single word

- Try to find the reason behind each aspect

- Consider whether the reason behind each aspect is still valid. Has changed since that attitude was formed, perhaps a situation or framework, etc.?

- Imagine that you have been asked to shape a new mental model based on each of the above aspects, and also taking into account the situation of today and tomorrow. Summarise the new mental model in a short sentence or a single word.

- Review stages 1-4 and draw your conclusions.

The process should work both when coaching one person or when working in a counselling role for a bigger group or company.

Sustainability – is this also relevant for leaders and managers?

In their book Sustainable Leadership , it is argued that resonance and empathy are the cornerstones of any leadership model because they make beneficial use (and not abuse) of the energy and mental resources of the employees, thereby keeping the whole organisation sustainable and taking energy, economy and power, etc. into consideration. This model suggests a 3-phase solution for an empathic process:

- Empathic understanding, empathic effort

- The affective – the receiver’s professional perception of emotions present

- The cognitive – the receiver’s handling of emotions, reflection and perspective taken

- Empathic behaviour

- Actions/gestures

- Communication

- Constant and continued validation and evaluation of the phases 1 and 2.

Something to consider: is sustainable leadership actually sustainable when it comes to mental, social and corporate resources, or is it just recycling, re-using and reflecting?

Further considerations regarding mindset, leadership, and emotional intelligence

This study leaves us with some ongoing questions that need to be discussed.

Think about your mindset in terms of the metaphor of a car. What is…

- the clutch? (can be activated for mindfulness)

- the brake?

- the motor (diesel/gas/hybrid)?

- the inner atmosphere, caused by the passengers, the climate – and the A/C?

We invite you to reflect on the following questions about emotional intelligence, emotions, and mindsets:

- How far can emotions be categorised in terms of mindset types?

- Can you change someone’s mind from the outside, or can only the individual themselves decide to change their own perspectives and mindset?

- How can a person change their emotions, using awareness of the basic mindset?

- How can a person, or a particular group of people, impact the emotions and mindsets of others?

- Is a mindset always fixed or can it become flexible through ‘brain agility’ or coaching?

- How can you train emotional flexibility when it comes to leadership performance?

Bibliography

- Anderson, Dean & Anderson Linda A. (2010): Beyond Change Management. Pfeiffer

David, Susan and Congleton, Christina (2015): Emotional Agility. In: Hayes (2015) Emotional Intelligence. Harvard Business. - Dweck, Carol S. (2006): Mindset. Random House.

- Gardner, Howard (2006): Changing Minds. The Art and Science of Changing Our Own and Other People’s Mind. Harvard Business School Press.

- Gardner, Howard (2008): Five Minds for the Future. Harvard Business School Press.

- Goleman, Daniel et al. (1998) Best of HBR on Emotionally Intelligent Leadership. Harvard Business Review.

- Gosling, Jonathan and Mintzberg, Henry (2003): The Five Minds of a Manager. In: Harvard Business Review, November 2003

- Jensen, Rolf (1999): The Dream Society. How the coming shift from information to imagination will transform your business. McGraw Hill

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types (Collected works of C. G. Jung, volume 6, Chapter X) Princeton University Press.

- Kolind, Lars (2006): The Second Cycle. Wharton School Publishing

- MacGregor, Douglas (1960): The Human Side of Enterprise.

- Stubberup, Michael og Hildebrandt, Steen (2012): Sustainable Leadership. Leading from the Heart. Copenhagen Press.

Anne Rise

Experiences throughout my life have contributed to my current passion for the development of individuals, whether in a professional, organisational, or personal setting. I have 45 years of experience as a leader in volunteer NGOs, 30 years of experience with training volunteer leaders, 15 years of experience training corporate teams and leaders, working with teams in the areas of creativity, networking, coaching, communication, competence building and personal development issues in many aspects. I have a bachelor’s degree in librarianship, coupled with a study in psychology and a master’s degree in organisational learning and working environments.

Experiences throughout my life have contributed to my current passion for the development of individuals, whether in a professional, organisational, or personal setting. I have 45 years of experience as a leader in volunteer NGOs, 30 years of experience with training volunteer leaders, 15 years of experience training corporate teams and leaders, working with teams in the areas of creativity, networking, coaching, communication, competence building and personal development issues in many aspects. I have a bachelor’s degree in librarianship, coupled with a study in psychology and a master’s degree in organisational learning and working environments.

I am also certified for a number of international personality assessments and coaching methods.

I am a freelance leadership and communications consultant, a coach and lecturer in leadership, personal development, and communication. I am currently also working as a leadership consultant for NGOs and teaching in business schools and at the University College South Denmark. I am also the volunteer vice president of alp.