Emo(tiva)tion – a leadership skill?

The relationship between emotions and motivation

Aim

Is motivation an emotion? It could be regarded as such when motivation is the drive that makes a person act or react. There are two aspects to motivation:

- An individual’s inner drive as they (re)act

- The impact of one person (e.g. a leader who inspires or motivates) on someone else

The aim of this article is to

- Describe the most relevant theories about motivation in leadership, taking emotional intelligence into account

- Take recent brain studies about emotions and motivation into account

- Mention a few models that can help leaders who are leading with emotional intelligence

Emotionally intelligent leader is aware of their own emotions and can make use of this knowledge to understand the emotions and motivational reactions of their followers. The emotionally intelligent leader Is constantly reflecting on which situations are arising and on the corresponding different reactions. These prompt thoughtful reflection by the leader about which emotions could be causing the behaviour that they observe.

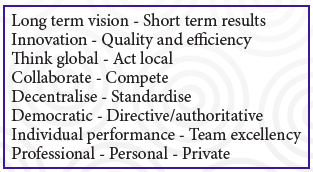

Any leader will face a number of personal and professional paradoxes on a daily basis, for example:

- trust vs. control

- being popular vs. being unpopular

- job security vs. new challenges

- personal interests vs. company interests

- optimism vs. a focus on the problems

Do leaders also take into account the paradoxes that their employees/followers are also facing as they try to do their best? Reinhard Pekrun has set up a model to show the links between environment, appraisal (motivational impact), emotions, and performance (table 1). This table also shows the cognitive complexity of elements that have a mental or physical impact on performance at work.

Another article discusses the various mind-sets and perspectives of leaders and followers. This systemic perspective is familiar to leaders who struggle to be viewed as the “ideal leader” by their company/organisation and their followers.

The dilemmas of the modern leader are described very well by Robert E. Quinn in his model ‘Competing Values Framework’.

The model ends up giving 4 main modern leadership roles, the most interesting of which for our purposes is the human relations model as mentor or facilitator.

Being a mentor (i.e. an experienced role model who gives advice to their mentee on the basis of their own experiences and evaluations) requires a conscious awareness of both one’s own emotions and of the impact that the mentorship is having on the motivation of the mentee. A mentor can easily demotivate a mentee if they illustrate their advice with old-fashioned or out-of-date examples of what could go wrong. The mentor should focus instead on situations where even insecure courage has led to fantastic results, motivating the mentee to be courageous and keep on trying. For example:

Edison tried to make a copper thread glow more than 6000 times before he succeeded. Imagine what would have happened if he had given up after 500 trials?

Facilitating someone else’s development (whether they are a learner or follower) means ‘meeting that person where they are’:

If one is truly to succeed in leading a person to a specific place, one must first and foremost take care to find them where they are and start from there

Facilitating is therefore closely connected to coaching, with a learner-centred perspective on investigating the aims, skills and competences that are already present, as well as the motivation and willingness to move on and develop.

Reactions and emotions

We all react in certain ways to a given current situation, mostly in line with previous reactions to similar situations that come to mind.

K. Friston has described how a model of ‘free energy’ in a given situation (whether linked to leadership, learning or working) depends on both the mental, intellectual, and social impact of those involved. This means that our current motivation for acting or reacting depends on the situation itself, the people present, and any previous experiences of similar situations or people.

When dealing with motivation, we must also consider both positive and negative stress as a form of motivation or de-motivation. Negative stress can be regarded as a destructive emotion, destructive towards both the activity and the person carrying out the activity. Positive stress can lead to a feeling of flow, a highly motivating emotion that can keep up energy even when none is left.

Mihalyi Csiksentmihalyi is well known for his model of stress and flow based on studies and articles about happiness, positive psychology, motivation, leadership and dealing with individual feelings. Aniston depicted a scale of stress levels and emotional existence with numerous models to describe the 3 corresponding mental states. They are most commonly referred to as the comfort zone, the learning (or growth) zone, and the panic zone. These illustrate how stress levels and emotional motivation are closely linked with each other.

States of mind / states of leadership

So which kind of leadership behaviour is most motivating and therefore most efficient for which kind of followers and for which kind of work? And how can leaders become more skilled at motivating their followers without causing negative stress? Can a leader’s own enthusiasm impact the motivation of the follower?

Engaged leaders are able to create engaged states in the brains of other leaders.

Trust among team members can be measured in heart beat synchronization among team members.

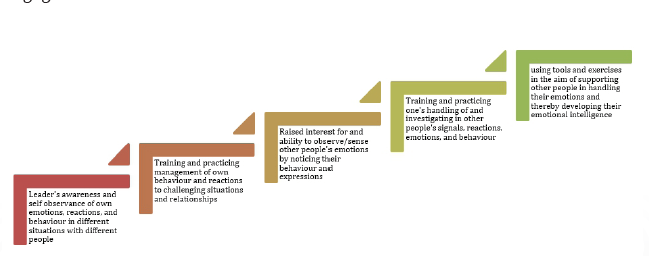

Becoming an emotionally intelligent leader means progressing up the following ladder of emotional intelligence and awareness:

Emotionally intelligent leaders should be constantly practising their abilities of observation and motivation as they become better at showing an emotional awareness of those around them. This awareness can be described as ‘positive interest’ that makes others feel valued by their leader.

High-EQ leaders also don’t make assumptions about how others like to receive communication from them. For instance, some people might appreciate face-to-face conversations while others prefer a simple text message.

The main tool for an emotionally intelligent leader is communication, active listening and supportive questioning/coaching to support the independent interest and conscious or mindful reflection of the follower. This is very different to the traditional leadership approach of control and criticism used by the X-perspective leader.

- Emotionally intelligent leaders want to know about those preferences so they can adapt their communication style for each individual on their team.

- Emotionally intelligent leaders typically possess another valuable soft skill: communication know-how. They also understand that it can be challenging for others, and they’d never make assumptions based on a colleague’s words. “Tell me more about that,” or “What did you mean when you said/did that?” is a judgment-free way to get clarity, says Dr. Neeta Bhushan, emotional health educator and author of “Emotional GRIT.” When leaders use these words, they are operating from a place of curiosity and compassion instead of judgment, she says.

- “The phrase ‘can you say more about that’ demonstrates a desire to better understand what the other person is saying or trying to get at, but is non-evaluative,” adds Drew Bird, founder at The EQ Development Group.

- Feedback is a two-way street for high-EQ leaders, says Ellis. “Emotionally intelligent leaders are inclusive by nature and never stop looking for opportunities to bring the thoughts and views of others into a discussion,” he says. “They recognise that they are not the smartest people in the room and look for ways to elevate others.”

Conclusion

To answer the initial question of whether motivation is an emotion or not, we could point to the fact that leadership is about a two-sided awareness of the emotions involved in any task or relationship. It is essential that any leader develops a conscious appreciation of existing feelings both for and against any familiar or unknown challenges that arise. The relations between stakeholders are an essential component of this appreciation and should be continually developed by any leader.

Bibliography

- Arnsten AFT (2009) Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. In: Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10(6):410–422;

- Arnsten AFT, Wang MJ & Paspalas CD (2012): Neuromodulation of thought: Flexibilities and vulnerabilities in prefrontal cortical network synapses. In: Neuron. 76(1):223-239

- Cameron, K.S., Quinn, R.E., DeGraff, J., and A.V. Thakor (2006) Competing Values leadership: Creating value in organizations, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (2003). Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning. Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-465-02608-7

- Friston K, Kilner J & Harrison L (2006) A free energy principle for the brain. In: Journal of Physiology – Paris 100:70–87;

- Friston, J. Karl & Stephen, E. Klaas (2009): Free-energy and the brain, In: Synthese. 159(3):417-458.

- Friston KJ, Daunizeau J, Kilner J & Kiebel SJ (2010): Action and behavior: a free-energy formulation. In: Biol Cybern. 102(3):227-260.

- Friston K (2012): Prediction, perception and agency, In: International Journal of Psychophysiology. 83:248–252.

- Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R.E. and McKee, A. (2002): Primal Leadership: Realizing the Power of Emotional Intelligence. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

- Gross, J. (1998) The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Review of General Psychology. 2(3):271–299.

- Handbook of Competence and Motivation. Theory and Application. Ed. By Elliot, Andrew J., Dweck, Carol S., and Yeager, David S. (2017) 2nd ed. Guildford Press.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1858): English translation by Hong & Hong, The Point of view for my work as an author, Princeton University Press, 1998, chapter IA, §2, p. 45:

- Lewis, M.W. and G.E. Dehler (2000): Learning through paradox: A pedagological strategy for exploring contradictions and complexity, Journal of Management Education, Vol. 24: 708-725.

- Lüscher, L. & M.W. Lewis (2008): Organizational Change and Managerial Sensemaking: Working Through Paradox, In: Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51, No. 2, 221-240.

- Mercier H & Sperber D (2017) The enigma of reason. Allen Lane.

- Okon-Singer H, Hendler T, Pessoa L & Shackman AJ (2015) The neurobiology of emotion–cognition interactions: fundamental questions and strategies for future research. In: Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00058

- Pekrun, Reinhard (2017): Achievement Emotions. In: Handbook of Competence and Motivation. 2nd ed. London, Guilford Press. Chapter 14

- Porges, Stephen (2001) The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social

nervous system. In: Int. Jour. Psychophysiology (42)2:123-146. - Quinn, R. E., Faerman, S. R., Thompson, M. P., & McGrath, M. R. (2003). Becoming

a Master Manager: A Competency Framework (3 Ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons. - Quinn, Robert E. (1988) “Beyond rational management: Mastering the paradoxes

and competing demands of high performance”, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, USA. - Tomm, Karl (1988) “Interventive Interviewing: Part III. Intending to Ask Lineal,

Circular, Strategic, or Reflexive Questions?” Family Process, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1-15.

Links

- https://di.dk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Global%20Leadership%20Academy/Paradoxes-

koncept/Paradoxes%20in%20a%20global%20world%202014%20-%20ver%202.pdf - https://josephnoone.com/2016/01/31/simplicity-beyond-complexity-the-competing-

values-leadership-framework/ - Rudder, Carla (2018(I)): 8 Powerful Phrases of Emotionally Intelligent Leaders

https://enterprisersproject.com/article/2019/2/emotional-intelligence-8-go-phrases-

leaders - Rudder, Carla (2018(II)): 10 Things Leaders with Emotional Intelligence Never Do.

- https://enterprisersproject.com/article/2018/4/10-things-leaders-emotional-intelligence-never-do?sc_cid=70160000000cYRWAA2

- 5 TED talks to increase your Emotional Intelligence https://enterprisersproject.

com/article/2018/1/5-ted-talks-increase-your-emotional-intelligence

Anne Rise

Experiences throughout my life have contributed to my current passion for the development of individuals, whether in a professional, organisational, or personal setting. I have 45 years of experience as a leader in volunteer NGOs, 30 years of experience with training volunteer leaders, 15 years of experience training corporate teams and leaders, working with teams in the areas of creativity, networking, coaching, communication, competence building and personal development issues in many aspects. I have a bachelor’s degree in librarianship, coupled with a study in psychology and a master’s degree in organisational learning and working environments.

Experiences throughout my life have contributed to my current passion for the development of individuals, whether in a professional, organisational, or personal setting. I have 45 years of experience as a leader in volunteer NGOs, 30 years of experience with training volunteer leaders, 15 years of experience training corporate teams and leaders, working with teams in the areas of creativity, networking, coaching, communication, competence building and personal development issues in many aspects. I have a bachelor’s degree in librarianship, coupled with a study in psychology and a master’s degree in organisational learning and working environments.

I am also certified for a number of international personality assessments and coaching methods.

I am a freelance leadership and communications consultant, a coach and lecturer in leadership, personal development, and communication. I am currently also working as a leadership consultant for NGOs and teaching in business schools and at the University College South Denmark. I am also the volunteer vice president of alp.